D-Day remembered …

D-Day remembered …

By Karen Clem Fritz

Reprinted from the June 5, 1999 issue of ExPRESS

“As our boat touched sand and the ramp went down I became a visitor to hell.”

-Pvt. Charles Neighbor, 29th Division, Omaha Beach

The news the free world had been waiting for at the height of World War II was broadcast at 9:33 a.m. London time, June 6, 1944 while most Americans were sound asleep.

The brief press release said, “Under the command of General Eisenhower Allied naval forces, supported by strong air forces, began landing Allied armies this morning on the northern coast of France.”

The event, which took place 55 years ago tomorrow, became known simply as D-Day.

The invasion of the Normandy coast of France by the Allied Forces which had banded together to defeat Nazi dictator Adolph Hitler remains the largest build-up and movement of soldiers in the history of mankind. It also marked the beginning of the end of Hitler’s brutal five-year grip on Europe.

The German military had long anticipated and prepared for the Allied invasion. Under the direction of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, a cruel collection of beach obstacles, mine fields and artillery lined the coast of France. “Never in the history of modern warfare had a more powerful or deadly array of defenses been prepared for an invading force,” wrote Cornelius Ryan in his 1959 book The Longest Day.

After many months of meticulous planning and excruciating efforts to keep the massive force, as well as the date and exact location of the planned invasion, a secret from the Germans, “Operation Overlord,” the code name for the invasion, was launched with more than 5,000 ships, 10,000 airplanes and 250,000 service men and women – many of them not yet 20 years old.

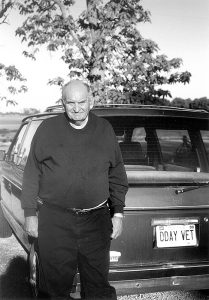

Among the troops was a 19-year-old rural Winamac farm boy, Gerald, Rife, who, over his father’s objections, had joined the army 11 months earlier before completing high school.

“Dad was 100 percent against me going to the war,” Rife said, “and he had put in for a farm deferment for me.”

But Rife’s older brother was already helping on the family’s 400-acre farm on a deferment, and Gerald believed that “anyone with any gumption went into the service. I still think so.”

So Rife enlisted in the army in July 1943 and was sent to Fort Bragg in North Carolina where he immediately began training for combat duty as a sniper and machine gunner. He says he knew from the beginning that he was being trained for what everyone in the world knew must eventually come – the invasion. The training was rigorous and often featured sleepless nights.

In February 1944, Rife was sent across the Atlantic Ocean to Wales, and then England for extensive training and practice landings on shore.

Rife recalled that the men in his unit did not know the extent and details of the “whole invasion picture.” They only knew their own assignments.

In the final months before the invasion the build-up of troops, weapons and equipment along the southern coast of England was enormous, and the invasion participants found themselves in a strange world in these restricted areas which were sealed off from the rest of the country under a tight curtain of security.

Congestion in these coastal areas was a major problem, Ryan wrote in his book. “Chow lines were sometimes a quarter of a mile long. There were so many troops that it took some 54,000 men, 4,500 of them newly trained cooks, just to service American installations.

By the end of May, Rife said the troops “knew the time for the invasion was getting close.”

Loading of troops and supplies onto the transports and landing ships began during the last week of May.

“There was much anticipation,” Rife remembered. “Chaplains were constantly visiting the troops. Then they fed us a meal and loaded the boats.”

The U.S. loaded 74,000 soldiers bound for Normandy to secure two code-named beaches, Utah and Omaha. They joined 83,000 men from other Allied forces (mostly British and Canadian) who were to establish themselves on three other beaches farther east along the coast – Gold, Juno and Sword.

Rife said he was a member of a unit of 200 snipers and machine gunners who had trained together, beginning at Fort Bragg. They belonged to the U.S. Army 1st Infantry Division forces. Rife and 29 other members of his unit boarded a transport, LST 355, bound for the “Easy Red” sector of Omaha Beach. “H Hour” would be 6:30 a.m.

“We left just a couple of hours before dawn,” Rife recalled. The invasion had already been postponed a day due to stormy weather in the English Channel, but Rife cannot remember if the weather was still cloudy and rainy. “I’m not sure; I believe so.”

Rife said everyone was quiet during the trip across the Channel. “We had practiced the landing lots of times. We knew we had plenty to do and everything had to be fresh in our minds.”

The Germans had also practiced maneuvers to repel the anticipated invasion. Then during that historic night they were alerted to scattered reports of Allied paratroopers landing in the fields behind the Normandy beaches. Suspicions aroused, they manned their positions along the fortified coast, although most Nazi officers at this point believed that this initial Allied activity was most likely a diversion from the “real” invasion which was expected farther east along the coast at Calais.

Then in early dawn, just before the sea landings, Allied bombs began to fall along the Normandy coast in an attempt to knock out the bunkers housing the gun power above the beaches.

But at Omaha Beach everything went wrong. Scattered cloud cover prevented the 329 bombers assigned to destroy the menacing guns at Omaha from unloading their 13,000 bombs on target. Most fell up to three miles inland. Then special amphibious tanks that were supposed to support the landing troops at Omaha sank in the choppy waters as they were unloaded. Only two of the 29 launched made it to the beach.

So the Americans landing at Omaha faced, without support, the veterans of the Nazi 352nd Infantry Division and their deadly guns aimed at the beach.

Rife said his LST was among the first to approach the shore. “We were 100 yards away at most when the Germans opened fire.”

At this point the invaders’ training came down to “jump, swim, run and crawl to the cliffs,” explains literature from the National D-Day Memorial Foundation.

As were his fellow troopers, Rife was weighed down with weapons and gear. “Our guns were all cosmaline (water-sealed). I carried everything from my SAR (sniper army rifle) down to a .32 automatic and small carbine, plus ammunition and hand grenades.” He also carried his canteen and musette bag with rations. The soldiers’ equipment weighted a minimum of 30 pounds and sometimes one-and-a-half times more, according to Rife.

Fortunately, even with all his heavy equipment, Rife was “tall enough that I didn’t go clear under the water” when he unloaded under German fire from his LST. One of the next things he recalls was that there were “a lot of rocks” under the water to walk around.

Rife had entered a killing zone which would from that day forward be known as Bloody Omaha.

“I was ducking fire the whole time,” Rife continued. He managed to wade through the spray of bullets and find cover in the water behind a rock where he began to shoot back at the Nazis.

He estimated the beach was about 100 feet across, behind which rose a bluff about 25 feet high, lined with hedgerows.

The horror of what Rife saw and experienced through the rest of D-Day on Omaha Beach is a story he has never shared with anyone in the last 55 years – and never expects to.

In response to gentle questions of what happened next, he simply looks down and away, and acute pain visibly spreads across his face. (Rife only agreed to this interview at the request of his youngest daughter who is proud of her father and believes that as much of his story as he is willing to share should be told.)

Pinned down by German gunfire, Rife said he spent the next five or six hours trying to get out of the water. A state of confusion and shock prevailed. Officers were killed and soldiers found themselves alone and separated from their units. They sought refuge behind deadly beach obstacles and contemplated the deadly sprint across the beach to the base of the bluffs. Bodies lay on the beach or floated in the water. Destroyed landing craft and other vehicles littered the shore. At 8:30 a.m., all landing ceased at Omaha.

The cause was feared lost.

But slowly, through sheer courage and determination – and even anger – small groups managed to cross the beach and make their way up the bluffs. At the same time, navy destroyers moved into shallow water, scraping their hulks, and blasted away at the Nazi guns at point-blank range.

“By nightfall, the situation had swung in our favor,” Gen. Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. first Army later said. “Personal heroism and the U.S. Navy had carried the day. We had by then landed close to 35,000 men and held a sliver of corpse-littered beach five miles long and about one-and-a-half miles deep. To wrest that sliver from the enemy had cost us possibly 25,000 casualties. There was now no thought of giving it back.”

Day blended into night for Rife. He soon realized the benefit of his sleepless basic training at Fort Bragg. Many such days and nights later he arrived in St. Lo, a small French town that he remembered had been “blown to pieces.” There soldiers were reorganized into new units and began their march toward Germany.

Rife’s unit was among the first to arrive in Paris for the liberation of that city. He participated in the Battle of the Bulge. The first Nazi concentration camp he came across was in Belgium. He eventually marched across Germany and met up with the Russian Allies in Czechoslovakia.

But none of these experiences and following battles compared with D-Day. “Nothing else after that even came close,” Rife insisted.

In the 55 years since that day, Rife never slept through a night. He wife, Mary confirmed this. She remembered one night early in their marriage when he awoke from a nightmare and dove under the bed.

To this day, Rife remains haunted by his D-Day memories. “It would be nice to take a pill and forget it all,” he said quietly.

The price the Allies paid at D-Day was brutal. Casualties numbered nearly 10,000. Ninety percent of American casualties were sustained at Omaha Beach. U.S. casualties on D-Day totaled 6,603, including 1,465 dead.

But had the invasion failed, experts believe it would have taken several more years to defeat Hitler and his Nazi armies.

At the end of World War II only 15 soldiers from Rife’s 200-member unit came home. At the time of this interview, he was one of only two still living. For over 50 years, only Rife’s closest family members knew he was a D-Day participant. He doesn’t want to see movies or read books about the invasion, or visit Normandy or meet with other war veterans. He really doesn’t care to be reminded of the invasion.

“The tales of loss and heroism of D-Day are countless as the grains of sand on the Normandy coast,” observes the National D-Day Memorial Foundation.

That’s why on the anniversary of D-Day, it is vital that the rest of the world remembers what Omaha Beach veteran Gerald Rife cannot forget.

Note: Gerald L. Rife passed away Sept. 13, 2000.