Reprinted from the Independent, Pulaski County A-Z “Tt” – 20 in a series of 26, by Jim Carr and Alan McPherson, Monday, July 20, 2002.

(Photos have been changed.)

Tippecanoe. This humble stream has helped elect a national president and named a small species of fish unique to its waters. Meandering through eight of Indiana’s northern counties, the Tippy, as it is fondly called, becomes a “liquid necklace,” stringing together its pearls along the way. Its name is attached to villages, towns, cities, townships, counties, lakes, battlefields and parks along its path. Early treaties use it as a reference point on the face of a poorly mapped, infant state. Famous as a battlefield, just a few years later, it was ignored as America attempted to connect the Atlantic with the Gulf of Mexico by a system of waterways. Now, it is globally recognized as one of the nation’s most important rivers. Here in Pulaski County, it is certainly our most storied, and important body of water.

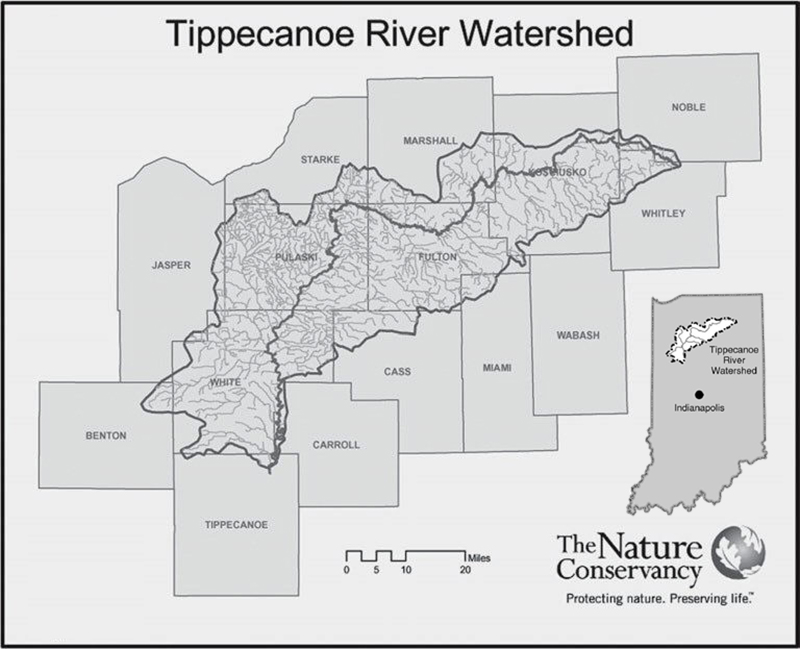

Rising as a thin ribbon of water out of Little Crooked Lake along the border of Noble and Whitley counties, it begins its 166-mile trek to its confluence with another of Indiana’s rivers, the Wabash. In its infancy, the Tippy connects several spring-fed lakes – Crooked Lake, Big Lake, Smally Lake, Baugher Lake, Wilmot Mill Pond, Webster Lake, and Lake James – before leaving Tippecanoe Lake and actually taking form as a true river. From southwest through the Maxinkuckee Moraine and the counties of Elkhart and Kosciusko until it reaches Pulaski County, which contains more than 40 meandering miles of the Tippy, including a brief brush with Starke County. Then it’s on through White County and Tippecanoe County, forming the western boundary of Carroll County along the way. It is along that route that the first settlers of this area made their homes – and left their mark – long before history was written down.

Evidence of earlier occupation remained when white men came to build homes in the wilderness along the Tippecanoe. Early local accounts speak of possible burial mounds built by what may well have been Pulaski County’s first inhabitants. In his Century of Achievement, written for the centennial year of 1938, the late Judge John Reidelbach mentions “nine or 10 earthen mounds” along the Tippy’s shore. Two Indian skeletons, he writes, were unearthed from one of these, located on a 10-acre farm about a mile east of Winamac. The origin of these mound builders is only speculation, and no one has any idea what they called the stream they settled on and later left. Later Native American inhabitants, the Miami and the Potawatomi, also left their mark, as Judge Reidelbach notes. Early white settlers encountered tribal remnants and found places where the natives met for council fires, danced and built dams for the purpose of easy fishing. It is these later tribes who give the Tippy the name it’s known by today.

Although rivers and streams were native American highways, the name Tippecanoe has nothing to do, as some might imagine, with an unstable Indian watercraft. The Miami Indians – at one time Indiana’s largest tribe – were first in the territory and named the river Ki-kap-kwan. Their later neighbors, the Potawatomi, called it Ki-tap-i-kon. In both native languages, the name means “buffalo fish.” This species of sucker, according to Webster, is named for the hump on its back, which evidently reminded the Indians of a buffalo’s shape. As white men struggled to pronounce these Indian versions, the best they could do was Tippecanoe, and the name remains. Although the Tippecanoe formed a sort of boundary between the Miami to the south and east and the Potawatomi to the north, it bore no particular significance in history until two members of another tribe brought it to national prominence by settling on its banks.

Tecumseh, Shooting Star, and his brother Tenskwatawa, Open Door, were sons of a Shawnee father and a Creek mother. Born in Ohio, they eventually settled, along with a hodgepodge of followers from various tribes, just north of the mouth of the Tippecanoe on the site of former Miami and Potawatomi villages, located near present day Battleground.

Tecumseh, sometimes also known as Panther, has been depicted historically as the archetypal noble savage. Well-built and handsome, he had been a warrior and hunter from an early age. But, he is most famous for his persuasive speeches and political skills among other tribes.

In appearance, Tenskwatawa was small and frail, known in his tribe as “The Loud Mouth.” During his childhood, an accident with an arrow blinded his left eye. Depth perception marred, he was a failure as a hunter and warrior. He has been depicted as cowardly, fighting in just one battle in his early life, preferring to stay at home in the safety of camp. Not a hunter or raider, and with no visible means of support, he was unable to find a wife or take any position of authority among his people. Eventually, he fell under the influence of the white traders and strong drink, becoming a drunken “hangabout,” begging for his keep around early settlements, trading posts and forts. Then, during a particularly desperate binge, Loud Mouth had a vision. He stopped drinking and, briefly, was converted to Christianity by Moravian missionaries. Returning to his tribe, he shared his vision with his brother. According to his vision, Indians could regain their lost lands and drive out the white man by returning to their native ways. His message, spread mostly by Tecumseh, attracted many followers. Now fully a respected Indian shaman, he changed his name to The Open Door, but the white settlers called him the Shawnee Prophet.

The Prophet’s vision that Indians should forsake all things that were provided by the whites, including dress, food, liquor and weaponry, inspired many disenfranchised Indians. If returning to native ways would get rid of new, white Americans from encroaching upon their lands, the Native Americans were ready. But the Prophet’s coup de gras, which made him a legend, came from knowledge gained from the whites. Using some celestial information gained while living among the Moravians, The Prophet accurately predicted an eclipse of the sun. He told anyone who would listen that he had the power to block out the sun, and a couple of days later, he went into a meditative state, chanting and praying until a full eclipse of the sun arrived right on schedule. With a bit of trickery, he became a celebrity, revered among the Indians and feared for his influence over them by the whites. More and more natives from several Midwestern tribes flocked to join the Shawnee brothers and get ready to rid themselves of white influence and regain their own waning power.

For a while in the later 1700s, an Indian confederacy led by the Miami war chief Little Turtle had turned back several American advances. Through military strength, the Miami Confederacy managed to retain much of their lands in western Ohio and most of Indiana. But near the close of the century, they were defeated decisively by General “Mad” Anthony Wayne. The Confederacy scattered, but many of its members found solace with Tecumseh and The Prophet. Considered a threat to the peace of the frontier, the brothers were pressured out of their new home near Greenville, Ohio. Tecumseh, in his travels, had made friends with an influential Potawatomi chief. The chief offered them one of his villages, located on the Tippecanoe. By 1803, the Shawnee brothers had become part of Indiana’s history.

While the Shawnee brothers preached that no Indian could sell land, William Henry Harrison, the first Governor of the new Indiana Territory, was “buying” more from other Indian tribes who lived within the borders of the state. From his territorial capital in Vincennes he had, by the time the Shawnee brothers and their followers settled in at Prophetstown along the Tippecanoe River, negotiated two treaties which put most of southern Indiana under his control.

Prophetstown continued to swell in population as disgruntled young warriors from the Potawatomi, Miami, Wyandot, Chippewa, Winnebago, Moscoutan, Fox, Sauk, Ottawa, Shawnee and other Great Lakes tribes came to hear the back-to-basics message of The Prophet. Land hungry white settlers in the area complained loudly of the increase in Indian population and of roaming bands who were stealing horses and threatening warfare against frontier settlements. These complaints eventually caught the ear of General Harrison.

[From the editor of this piece in 2022: In 1811, the land was still several years away from a treaty with either the Indiana Territory or the US Government. The white settlers were trespassing on Native ground.]

A couple of attempts at peaceful agreements with Tecumseh and his followers in Vincennes went nowhere. Finally, Harrison prepared to march on Prophetstown and destroy it. His amalgamated army was a mixture of regulars, known as “Yellow Jackets” [a mounted militia company from Harrison County], Indiana militia and Kentucky volunteers. The force finally arrived at Prophetstown in early November of 1811. With Tecumseh away on a recruiting trip to add to the membership, The Prophet was forced to deal with Harrison and his troops on his own. Told by his brother not to get into any altercations while he was away, The Prophet rallied his followers to battle after an all-night prayer session. Neither a sneak attack or The Prophet’s incantations worked. The Indians were soundly defeated in a bloody battle, and their dreams of former glory were crushed. Prophetstown was burned to the ground. The Prophet, blamed by everyone present for the defeat, fled the scene. Harrison’s troops gave their leader the nickname of Ol’ Tippecanoe after this success at the Battle of Tippecanoe. The Tippecanoe Battlefield monument, located in Battleground, is now a public park dedicated to this battle.

Harrison served as territorial governor of Indiana but resigned in December 1812 to take part in the Northwestern Army in the War of 1812. He was elected president of the United States in 1841. While campaigning with his vice-presidential candidate, John Tyler, they used the motto, Tippecanoe and Tyler, too. Tecumseh, The Prophet and Harrison had made the Tippecanoe nationally famous.

The now-famous Tippecanoe was scouted as a possible canal route from Fort Wayne to Lafayette, but surveyors determined the volume of water to be inadequate to support any type of barge travel most of the year. But it was big enough to support some dams and races to power mills, and small settlements had already begun to grow up along its banks. More and more settlers required more and more land. The defeated Indians had little choice but to give it up.

Treaties were signed with the remaining tribes in 1818 and again in 1826. Each of these treaties mark the initial reference point as the Tippy. The Treaty of 1818 opens with “Beginning at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River…” while the Treaty of 1826 starts, “Beginning on the Tippecanoe River, where the northern boundary of the tract intersects… … Thence, up the (Wabash River) to the mouth of the Tippecanoe River.” In 1832, a third treaty, this time requiring removal of all remaining Indians, was signed. The treaty talks were held north of Rochester on an island in the Tippecanoe. So, in three of the final treaties with the Indians, the Tippecanoe plays a vital role. Indians were dispersed and the northern part of the state was thrown open to settlement.

The governmental office for selling and recording those newly opened tracts of land was located along the Tippecanoe River in the new town of Winamac. Cheap land brought more settlers into north central Indiana.

By the 1920s there was a need for electrical power in these rural, agricultural communities. Dams were built north of Monticello along the Tippecanoe to provide that power. Indiana was given carte blanche to begin producing electrical power as soon as possible. A by-product of this electrical expansion is Indiana’s premier amusement area. Two lakes, Freeman and Shafer, were created, and recreational cottage communities began to appear along the shores of these lakes and grew north along the river. Today, Indiana Beach is one of the largest recreational facilities in Indiana.

Recreation is, perhaps, the primary allure of the Tippy. It is home to a variety of fish and wildlife. Due to several factors, it is considered one of the cleanest rivers in the United States. Fed by so many natural springs at its source, it always has been considered too small a body of water to support large industry or be used for transportation. These contributing factors have allowed it to maintain relatively high water quality. This high water quality makes it home to two unique species of water wildlife – the clubshell mussel and the Tippecanoe darter. The clubshell’s presence, and its designation as an endangered species, brought the river to the attention of the Nature Conservancy, a global not-for-profit organization dedicated to “Saving the Last Great Places.” The Nature Conservancy has named the Tippecanoe as the eighth most important river in the United States because of the varied and unique species of aquatic wildlife it supports. The Nature Conservancy oversees the entire Tippecanoe watershed and is working on projects, such as reforestation of the river, to keep the water quality – and the Tippecanoe’s reputation as a river – high. Those who live and play along its banks make the river’s influence known by providing a name for many places along the way.

Tippecanoe River State Park near Winamac is one of northern Indiana’s premier state parks. Seven of Pulaski County’s 40 miles of shoreline is contained in the 2,761-acre park. Of that, 180 acres that border the Tippy are dedicated as a nature preserve.

Tippecanoe Township, which contains Monterey in the northeast corner of Pulaski County, also takes its name from the river. Tippecanoe Township was named due to the fact that it has the most miles of river frontage of any of the four townships through which the Tippy flows. Monterey also has a three-acre park, Kleckner Park, which features a boat ramp to the water.

South of Pulaski County, Tippecanoe County is home to Lafayette and Purdue University. There is also the village of Tippecanoe in Marshall County, and the settlement of Tippecanoe Shores near DeLong in Fulton County.

The Tippecanoe may be small by some standards, but in the history of Indiana and Pulaski County, it is a name to be reckoned with.